[Part 2] Why is maintaining roads hard?

How Ministry of Rural Development tripled annual road maintenance payouts for rural roads

This is Part 2 of a multi-part series covering why maintaining roads or infrastructure is a hard public policy problem and innovations in contract management and digital solutions that have seemed to help the Ministry of Rural Development and NHAI.

In the previous post,

I explained that default maintenance contracts are typically based on item rates, where the contractor issues bills according to the volume of work completed (both material and labor) for tasks such as filling potholes, repairing cracks, and clearing shrubs. There is a predetermined cap on the maximum amount that can be billed in a year. The process involves the contractor raising a bill, which then triggers the action of the government engineer. Upon receiving the bill, the government engineer is supposed to visit the site to verify the contractor's efforts. However, if the engineer fails to visit and document sufficient evidence in time, new potholes may emerge or shrubs may regrow by the following month, thereby complicating the verification of the work performed.

In summary, what are the characteristics of road maintenance?

Difficult to estimate work needed and depends on external factors (sudden rains, farm water spillage, heavy trucks, etc.)

Low ticket bills

A high number of recurring bills (60 bills over a 5 year period)

Difficult to prove work (not) done if inspections are not done on-time

Difficult to prove work was done upon future scrutiny

For government engineers, processing a maintenance bill is not only a difficult and risky task but also requires timely and regular assessments. These challenges are compounded by the context of poor state capacity, where government field officers are often overburdened and under-resourced. Additionally, they are frequently tasked with duties unrelated to their primary responsibilities, further complicating their ability to manage road maintenance effectively.

….

Therefore, there is a need to simplify, de-risk and unburden maintenance.

Introducing Outcome and Performance-Based Maintenance Contracts (OPMBC). In these contracts, the yearly estimate is divided equally into monthly amounts, and the contractor bills the full amount each month, regardless of the volume of work completed in that time period. The engineer's role shifts to evaluating the condition of the road on the day of their visit, focusing on the outcome rather than the quantity of work done by the contractor. This approach emphasizes the results of maintenance efforts and not the effort itself, thereby aligning contractor incentives with the achievement of desired maintenance outcomes.

The key building blocks for OPMBC-based routine maintenance are:

The contractor submits a full bill

There is a quantified marking criteria that measures the performance of the contractor or the maintenance outcomes.

Based on the marks, there is a mathematical formula that calculates the money to be deducted from the monthly bill.

For example, if the annual contract amount is Rs 12,00,000, this is divided into equal monthly payments of Rs 1,00,000 each. After say February, the contractor submits a bill for Rs 1,00,000, not based on specific efforts or materials but as part of the regular billing cycle. The engineer then evaluates the road in the first week of March, rating its condition on a scale from 0 (completely battered road) to 100 (perfectly maintained road).

Should the engineer rate the road's condition at 85 out of 100 for February, the contractor will receive a prorated amount of Rs 85,000. To discourage poor maintenance, a rule is established that if the road scores below 80, no payment will be made to the contractor for that month.

This approach eliminates the need for the contractor and engineer to quantify or verify the labor and materials for minor maintenance tasks, such as filling potholes. The contractor is responsible for submitting a full bill regardless of the specific work done, and the engineer assesses the road's condition, awarding marks based on the outcome at the time of the visit. The evaluation criteria for rural roads include a 100-mark rubric covering various aspects of road maintenance like main carriageway condition (30 marks), shoulder maintenance (20 marks) and jungle clearance etc.

Another, issue with earlier item-rate contracts was this:

Further, if the contractor doesn't raise a bill, it also reduces the engineer's incentive to inspect the road, leading to a situation where while no undue money is paid to the contractor, the road remains pothole-ridden, and the public suffer.

So if the contractor doesn't raise a bill, there is nothing for an engineer to measure and validate, and if the contractor then raises it later, the engineer is in a fix as to what to measure now. In many cases, this leads to maintenance bills just piling up for years, and engineers hoping they'll get transferred before a decision has to be made for those bills.

In this case, the engineer can keep recording the performance of the road at the end of each month, irrespective of whether the contractor will raise a bill or not. As long as the performance/outcome of the road is recorded every month, payment can be calculated whenever the bill is submitted.

But still, this doesn't solve all our issues. How does the engineer de-risk himself from future auditors? How do we de-risk future audits and add legitimacy to the measurement of performance?

Without the above problems resolved, PBMC remains a risky endeavor for the engineer.

Funnily, the Standard Bidding Document of PMGSY stated that the maintenance had to be PBMC more than a decade before it started getting implemented across the country.

Why?

One of the reasons was that the policy, while good on paper, didn’t have an adjoining IT intervention.

So how do we save evidence of performance?

As rural road routine maintenance largely deals with defects that are visible on the exterior of the surface, it makes it easier to record the condition of the road. You don’t need to click pictures of individual potholes or record measurements etc that were (un)filled, you just need to capture the general state of the road at the time of the visit. Stand in the middle of the road at a random location and click a picture. That would capture whether it is in good condition or not - at least for narrow rural roads.

So let’s design an IT intervention.

What if we allowed contractors to generate and submit bills online at a click of a button? As the bills are always the same fixed amount, this should be possible.

What if the engineer’s monthly inspections were through a mobile app that proposed system-generated locations on a road from where the engineer had to click geo-tagged pictures as proof of performance?

What if engineers could record marks online against the geo-tagged photographs captured during field inspections from the mobile app?

What if the final due amounts per month were auto-calculated by the system taking the above marks?

What if the bills were converted into payment vouchers with necessary taxes and state duties?

What if payments were deposited directly into the bank accounts of contractors?

So if we incorporate all these features, we get the Ministry of Rural Development’s solution called eMARG.

eMARG is designed to cater to the maintenance of 6,00,000 km of rural roads built under the Ministry of Rural Development’s PMGSY program. That’s a little less than 10% of India’s entire road network (urban and rural combined).

A quick video which explains everything I said till this point. 👇

A little history: eMARG was designed and developed by Madhya Pradesh Rural Development Agency or MPRRDA which is the agency that implements PMGSY in Madhya Pradesh. While the construction cost under PMGSY is shared by the state and central government, the maintenance cost of roads is to be purely born by state governments. eMARG was developed by MPRRDA through its state office of NIC to solve the very problems we’ve been discussing. It was earlier only for rural roads in MP. It so happened that the boss-lady IAS officer incharge of MPRRDA, Ms Alka Upadhyaya, was transferred to Ministry of Rural Development to eventually head the National Agency in charge of PMGSY. She immediately decided to scale eMARG nationally so it can be used across all states for PMGSY.

Not only did the fate of maintenance of rural roads in India change thanks to her, but my fates changed too as Alka ma’am went on to become my mentor and the best-boss I could have for many years that have came after.

It all seems rosy but let’s tackle some caveats:

Q. Aren’t we rewarding the contractor with money even if he possibly didn’t do much work that month?

A. Well, as long as the road is in good condition during the engineer’s visit, the contractor will get the full amount whether they filled 0 or a 100 potholes. It’s a neat trick. Often the contractor who constructed the road is given the maintenance contract for the first 5 years (Defect Liability Period). That means if the contractor constructed a high-quality road, it will have fewer potholes and therefore will be rewarded with maintenance money with less efforts. But if the road is poorly built, the contractor will end up losing money during maintenance as well. This adds to the incentive of building good roads.

Q. Isn’t the performance criteria a little subjective? For eg. out of the 100 marks, 30 are for main carriageway. The policy doesn’t describe in detail how to distribute these 30 marks which could lead to subjectivity, especially given the rule that scoring less than 80 marks overall leads to no payment.

I had the same concerns when the project was being scaled from Madhya Pradesh to a national project. But, I was told that the subjectivity was strategic. The discretion was necessary and part of the design. If item-rate was precise, PBMC in the case of rural roads was designed to allow discretion and promote easier cash-flow.

You see there was already little incentive or money to be made by the contractor in maintenance. Compounded by the paralysis exhibited by engineers, most maintenance bills were either not submitted or cleared till the end of the contract. Additionally, you are trying to get a digitally-averse population (civil + rural contractors) to a new shiny IT system. There was dire need to make maintenance a liquid and free-flowing proposition and the policy-backed discretion provided the needed lubricant.

It was then decided that once maintenance was re-claimed to be an attractive proposition and contractors lured into the system, we would increasingly reduce the discretion (It did happen, we now run AI models on the images that get collected during inspection and are slowly moving towards a video regime).

Moving rural contractors and engineers into this new system was no mean task and took us some years and neat tricks but as both contractors and engineers benefited from this system, it slowly but surely got embraced.

Why is eMARG one of my top favourite e-governance projects?

It takes a good policy on paper and helps implement it on the ground.

It reduces administrative burden for both the contractor and the engineer. Amongst a sea of fraud-monitoring projects, this project targets the cause of poor maintenance and not the symptoms.

It was devised closer to where the action is. It took something devised and implemented at the state level and scaled it nationally (bottom-up). I’ve written previously about how the distance between the developer and how it leads to poor e-gov projects

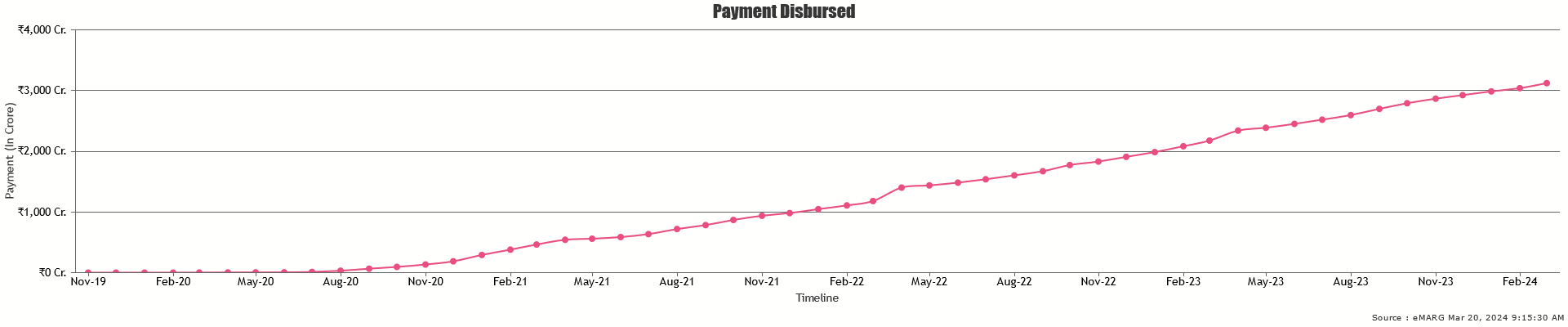

It led to tangible higher expenditure on rural road maintenance multi-fold the level of expenditure pre-eMARG.

Multiple states have moved to get their 100% state-funded rural roads too under eMARG as well. As the project is built by NIC and public-funded, we are sharing eMARG as a platform for other state schemes as well.

The act of digitizing the processes and generating transactional data of the processes, enabled deeper reviews and solidified maintenance in New Delhi’s and State HQs review agendas.

eMARG also got the second prize at the Government’s top e-governance awards for the year of 2021.

Parting Thoughts:

One would imagine that such important projects would have already been developed in India as it moves ahead with its digital ambitions. But this project is only 4-5 years old. Road maintenance is an age-old dusted topic, often spoken about in dining rooms, and helps garner votes too. But still, it continues to have scope for such policy and digital reforms.

This is my biggest concern with national digital imaginations being carried away with AI and other Bangalore market-led projects such as UPI, AA, etc. I believe they are extremely important as well, but there remains much left to do with boring old e-Governance and we shouldn’t move on too fast.

There is much left to do. eGov needs to be made cool again.

Next Part:

Does this work for National Highways? Simple visual performance criteria cannot work for National Highways with complex routine maintenance requirements and massive pay-outs. What are they up to?

Great article explaining the challenges for engineers in charge of rural roads!